4 Investigates: Red flag law failure

The 2020 law is meant to keep guns out of the hands of people who could be dangerous to themselves or others. In recent years, the law has been applied more frequently. On Feb. 1, 2024, for the first time, a man under an Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Order that barred him from possessing guns for a year, shot someone – himself – after police shot at him.

“He wasn’t this wild, crazy criminal”

Matthias Wynkoop was a roofer, a father, and struggled with depression.

“He was just a person in mental distress that needed help, and he didn’t get it,” his sister Marsha Torres said.

His family knew had been struggling with alcoholism, but he was trying to get help. They said he was seeing a therapist and receiving medication.

“He would call me when he got really bad,” Florence Thompson, his mom, said. “I would tell him, ‘Just come home. It’s fine. Just come home. And we’ll deal with it, we’ll talk about it.’”

Wynkoop’s criminal history shows a pattern of alcohol leading to trouble.

Oct. 25, 2023: Staff at a westside Albuquerque apartment complex called police because Wynkoop appeared drunk while waving a gun around. Albuquerque Police responded. Court documents show Wynkoop was shot with a less-lethal round from a 4o millimeter launcher. He was transported to the hospital and prosecutors charged Wynkoop with negligently using a deadly weapon.

Three days later on Oct. 28, 2023, police got a call about a suicidal man shot in the chest driving through town. According to court documents, a New Mexico State Police officer tried to pull over Wynkoop. He evaded the officer before eventually pulling over on I-40, stepping out of the vehicle and collapsing. He was not shot. The officer described smelling alcohol and hearing Wynkoop tell him, “Don’t make me do something stupid” while motioning to a pistol on the floorboard of his truck. The officer found 15 guns were found in Wynkoop’s vehicle. Wynkoop said he was meeting with a friend in Estancia to clean and work on his firearms. The officer started the Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Order process.

The DWI charge against Wynkoop was dismissed after NMSP failed to provide discovery.

The process

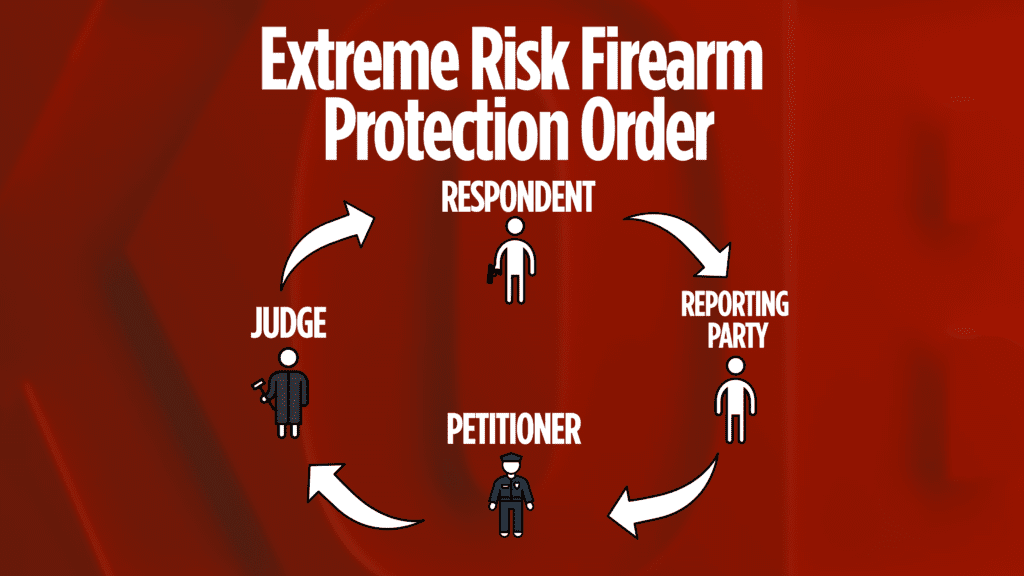

The law requires a reporting party to bring their concerns about someone with a gun (the respondent) to a petitioner. The petitioner brings the evidence to a judge. A hearing is supposed to be held within ten days after the petition is filed. A judge decides if a person should be barred from possessing guns for one year. The respondent then has 48 hours to surrender their firearms.

In Wynkoop’s case, the NMSP officer acted as both the reporting party and the petitioner, filing the petition on Nov. 3, 2023.

During a virtual hearing on Nov. 16, 2023, Wynkoop told a judge he had no firearms in his possession. He said he had been six months sober and relapsed. The judge commended Wynkoop for apologizing to the NMSP officer and getting treatment, but said “alcohol and firearms don’t mix” and granted the Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Order.

On Nov. 17, 2023, the judge filed the order barring Wynkoop from possessing firearms for a year.

Less than three months later Wynkoop died of a gunshot wound.

The appeal

The New Mexico legal system cannot agree on how the red flag law is supposed to work.

“The confusion is on reporting party,” New Mexico’s Solicitor General Alethia Allen said. “Understanding what the law is and how it’s supposed to be applied is always a good idea.”

Allen oversees all legal appeals for the Attorney General. That office is appealing a judge’s ruling in Santa Fe where she did not grant an Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Order because the Santa Fe Police Department acted as the reporting party and the petitioner.

“There’s a case where in Santa Fe the judge dismissed it on that basis alone,” Allen said. “We don’t agree with that interoperation.”

The appealed case in question has to do with a man with no criminal history. Santa Fe Police found him intoxicated, wearing camouflage and a bulletproof vest outfitted with ammunition on a walking trail near Cesar Chavez Elementary School. He did not have the gun on him at the time, but police found he owned two long rifles and two pistols and held anti-government beliefs. He told police he “thought firearms should be used to kill ‘bad people.’” Santa Fe Police temporarily confiscated his guns, but a judge denied granting the Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Order because the “Reporting Party does not have the required relationship with the Respondent.”

The data & impact

The red flag law is not applied widely, or often.

“The number of people it’s going to impact is small,” Allen said.

In 2023, in Bernalillo County District Court, 4 Investigates found 30 Extreme Risk Firearm Protection orders filed. In 20 of them, law enforcement acted as the Reporting Party and the Petitioner.

During the same time frame in Santa Fe District Court, only one Extreme Risk Firearm Protection order was granted — because the Reporting Party was someone’s mom.

In many parts of the state, there were no Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Orders filed in 2023.

The New Mexico Department of Justice is working to train law enforcement agencies on how to initiate Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Orders.

The failure to change the law

Efforts to amend the law in the latest legislative session failed.

House Bill 27 would have allowed law enforcement officers and health care professionals to act as the reporting party, answering the Santa Fe judge’s concern and clarifying what kinds of people can start the process. It would also have shrunk the time to surrender firearms from 48 hours to immediately, and centralized data collected on Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Orders into the National Crime Information Center.

The bill died on the House floor waiting for a vote.