4 Investigates: Is CARA helping or hurting families struggling with substance abuse?

It’s been almost a year since KOB 4 first raised concerns about a state program put in place to help New Mexico families struggling with substance abuse. The gaps in support are still there.

Now, more and more children are paying the sometimes-deadly price of drug addiction.

CARA is supposed to help moms and caregivers with babies born exposed to substances like drugs or alcohol. Instead of being reported for child abuse, parents and babies stay together.

They are supposed to get wraparound services – everything from addiction treatment to counseling or financial support. But what happens when families don’t get the help they need, and those babies go unreported?

KOB has reported on numerous infant deaths and infant/toddler drug overdoses and exposures in 2023:

- Mom charged with baby’s death makes court appearance

- APD: Woman charged for death of her 5-month-old child

- Local mother to remain in jail after toddler dies from ingesting cocaine

- Warrant issued for Albuquerque mother after toddler overdoses on fentanyl

- Police: Albuquerque parents in jail after toddler’s fentanyl overdose

THE COMPREHENSIVE ADDICTION AND RECOVERY ACT

“What’s my baby girl doing?” Larry Gallegos said to his 2-year-old granddaughter.

Gallegos now treasures every moment he gets with his grandchildren. In May, his 2-year-old granddaughter Marilena Gallegos nearly died. She overdosed on fentanyl.

“This was devastating to me,” said Gallegos. “It wasn’t eye-opening, I just could not believe it.”

Albuquerque police arrested Larry’s daughter, Chanel Gallegos, and her boyfriend, David Olivas, following that overdose, after officers discovered drugs in their home in reach of their children.

“In all honesty, she’s a good girl, a lot of people will vouch for that,” Gallegos said. “It’s just the drugs took them over and she didn’t get no help. She couldn’t get no help.”

But why not? Chanel’s struggles are not new. Marilena was born with drugs in her system.

Instead of reporting her for abuse based on that exposure, she should have been offered help. CARA, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, was passed in 2019.

It’s New Mexico’s version of federal legislation.

“The whole intent of it was family service,” said Interim CYFD Secretary Teresa Casados. “It’s a medical issue. We don’t want people to feel punitive about it.”

Under CARA, hospital workers create a plan of care. It’s a packet of resources and treatment options, but it’s all voluntary.

Then, a notification is sent to the New Mexico Department of Health and the Children Youth and Families Department.

Insurance company coordinators of managed care organizations (MCOs) take it from there, getting them plugged in.

Casados said it’s supposed to keep families safe, together.

“We want to make sure that they’re getting that care they need,” Casados said.

Since 2020, more than 3,700 have been created. However, making sure people are getting the care they need is where it falls short.

“The babies that are born substance abuse, the majority of those families are choosing to enter into a CARA plan,” Casados said.

But that just means the family agreed to services, of their choosing. It doesn’t mean that the family made an appointment or is actively engaged in that service. That’s not something that’s currently tracked by the state.

Casados said some of that follow up is part of the MCO’s responsibility, but MCOs do not have to submit a report to the state. So there’s not much data to show what happens to these families after they leave the hospital, and that includes when a child with a plan of care dies

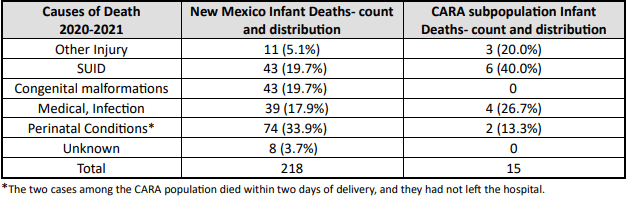

Casados couldn’t accurately tell 4 Investigates how many babies with a plan of care have died. We discovered that number is 15 for the years 2020 and 2021. Two of those babies died days after birth.

DATA COLLECTED BY THE NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

Data for 2022 was unavailable, so KOB went digging through autopsies. Of the reports we got back for 2022, we discovered 11 babies/toddlers under the age of 2 years old, died with substances in their system. Five other autopsies specifically mention prenatal exposure or parental substance abuse.

We found potentially 16 children in 2022. KOB asked Secretary Casados about that, and she responded hypothetically.

“The Plan of Care is optional, so if 14 of them chose not to have a plan of care, those individual babies wouldn’t be on our individual radar screen to go out and do an investigation,” Casados said.

While that is true now, prior to CARA passage, babies born exposed would require a report to CYFD for abuse. It would have possibly generated a follow-up investigation.

“I would say some of those babies would still be alive,” Joanna Rubi said.

Rubi is a former neonatal intensive care nurse and – for obvious reasons – a go-to foster parent.

“I think that the struggle right now is are these babies safe? If you don’t have resources, if these moms don’t have immediate resources. Is it good enough to send them home with a paper plan?” Rubi said.

She’s cared for more than 200 babies over the years – many experiencing some type of withdrawal. Those babies are often very difficult, and Rubi said, may challenge someone who is already struggling with substances.

“I have never had one phone call from managed care even mentioning this baby had a CARA Act,” Rubi said.

Her metro-area nurse friends tell her they’re in the dark too.

“To talk to the nurses in every unit and nobody knows what it is. We’re doing a disservice to the baby, to our nurses who help heal these babies, to the mom, and to this program,” she said.

She knows there’s not a simple answer.

“I think the things we don’t want to do with these moms is vilify them,” she said. “A lot of these moms have been trafficked, they’ve had horrible histories of sexual abuse, and the drugs are covering their pain. I’ve seen moms cry, weep when I walk out with their babies after a visit. These moms love their babies like I love my babies.”

SO WHAT’S NEXT?

Without follow-up, the nonpunitive approach can play out differently than intended. Instead of being vilified, moms are criminalized.

Larry Gallegos doesn’t know if his daughter had a plan of care but he does know no one ever reached out to them. Not after his granddaughter was born exposed or when she overdosed at four months old. Not until her near-deadly overdose at two.

“If you don’t follow up on that, they’re not going to go through it, especially if they’re struggling, you know what I’m saying,” said Gallegos.

Various state agencies play a role in this program. Agencies like CYFD, the Department of Health, the Early Childhood Education and Care Department, and Human Services. But perhaps the multi-agency approach is part of the problem.

“I think there’s a lot of confusion on who does what with respect to those individuals. One of the things we’re working on with the departments ECECD, DOH, CYFD, and HSD are all at the table right now. We’re mapping out what that looks like,” Casados said.

The Department of Health has hired a contractor to help sort that out.